It Awakens Every Sympathy of Our Hearts

Historical Background for Doctrine and Covenants Section 101

What is the historical background for Doctrine and Covenants Section 101?

In his book A Joseph Smith Chronology, J. Christopher Conkling shares the following timeline that leads up to the reception of this revelation:

Oct. 19, 1833

Governor Dunklin of Missouri answers the petition of the Saints, advising them to go to the local justices of the peace for protection and to sue in the local courts for property damage.

Oct. 20, 1833

The Church officials in Missouri announce their intentions to defend themselves, having purchased powder and lead in Clay County. The Missourians look upon this as breaking the treaty agreement of July 23, 1833.

Oct. 26, 1833

A mob of about 50 meet together and vote “to a hand to move the Mormons.” (CHC 1:343.)

Oct. 30, 1833

The Saints receive an offer from lawyers Wood, Reese, Doniphan, and Atchison to defend the Saints for the sum of one thousand dollars (two hundred and fifty dollars each).

Oct. 31-Nov. 7, 1833

The mobs begin a reign of terror in Missouri.

Oct. 31, 1833

A mob of 50 attacks houses west of the Big Blue River, whipping and stoning women, men, and children.

Nov. 1, 1833

On this Friday night, a mob moves to attack the Colesville Branch, which is located on the prairie about 13 miles west of Independence. Two advance spies contact Parley P. Pratt and hit him on the head with their guns, drawing blood. The other Saints are aroused and capture these two, keeping them for the night. This causes the rest of the mob to postpone their attack. Violence breaks out against the Saints’ homes in Independence. The home of A. S. Gilbert is destroyed. The Gilbert and Whitney store is destroyed; goods are thrown everywhere. Other houses are attacked and windows are broken, with Saints whipped and driven into the wilderness.

Nov. 2, 1833

The Saints in Independence move a half mile away from the city into the wilderness and camp there in groups of 30. Another mob attacks the Saints located on the Big Blue River, six miles from Independence. David Bennett, who has been sick in bed, is beaten terribly, and one of the mob receives a bullet in his thigh.

Nov. 3, 1833

Several Saints go to the justices of the peace, who refuse to issue peace warrants because they fear the mob. The friends of the Saints warn them to leave Independence at once because the mob has warned that tomorrow “would be a bloody day.” (HC 1:429)

Nov. 4, 1833

The mobs, 40 or 50 with guns, begin their destruction. They meet 30 Mormons, with 17 guns, led by David Whitmer. At sunset there is a battle, and two of the Missourians are killed (including one who had claimed, “With ten fellows, I will wade to my knees in blood, but that I will drive the Mormons from Jackson County”). Andrew Barber is also shot and dies the next day (the first Mormon to die in battle). Philo Dibble is wounded and lies dying for several days until Newel Knight administers to him; then Dibble immediately vomits up several quarts of blood and the bullet with which he was wounded. That evening the Gilbert and Whitney store is totally demolished, and several of the Saints are advised to go to jail, as that is the only safe place in town. Later that night, however, they return home. (HC 1:429-32)

Nov. 5, 1833

Early in the morning A. S. Gilbert, Isaac Morley, and John Corrill are taken to prison and shot at on the way. Rumors spread that Lt. Gov. Boggs is behind the mob. Rumors also spread that the three prisoners will be shot, and 100 Saints gather to protect them. Before a full-scale war breaks out, however, the Saints decide to surrender their arms if the Missourians also promise to disarm. The Mormons later discover that the leaders of these harassers seem to be Lt. Gov. Boggs, the Rev. Isaac McCoy, Judge S. D. Lucas, and almost every other local government official. In the evening of November 5 and 6 about 150 women and children flee to the prairie with only six men to protect them.

Nov. 6, 1833

W. W. Phelps, A. S. Gilbert, and William E. McLellin send a letter to Governor Dunklin explaining their side of the Missouri problems.

Nov. 7, 1833

The Saints are driven from Jackson County to Clay County, Ray County, Van Buren County (and from Van Buren County to Lafayette County). On both sides of the Missouri River, 1200 homeless Saints gather, destitute, camping out in tents.

Nov. 13, 1833

At 4:00 A.M. a meteoric shower fills the sky with “the falling of the stars.” The destitute Saints camped along the Missouri look upon this as a favorable sign from heaven. According to one source, in the fall of 1833 Joseph Smith, Jr., had prophesied, “forty days shall not pass, and the stars shall fall from heaven.” (HA 69; HC 1:439.)

Nov. 19, 1833

Joseph records some personal notes and his personal opinion of his counselors: Sidney Rigdon is a great and good man but has several faults so that one cannot place confidence in him; Frederick G. Williams “is one of those men in whom I place the greatest confidence and trust, for I have found him ever full of love and brotherly kindness.” (HC 1:443-44.)

Nov. 22, 1833

Don Carlos Smith, Joseph’s youngest brother, comes to live with Jospeh to learn the art of printing.

Nov. 25, 1833

Orson Hyde and John Gould arrive from Missouri to tell Joseph and the brethren in Kirtland the terrible news of the happenings there.

Dec. 1, 1833

Oliver Cowdery and Newel Whitney arrive in Kirtland with a press from the East.

Dec. 5, 1833

Joseph receives a letter from W. W. Phelps further outlining the Missouri persecutions. About this time Joseph writes Bishop Partridge in Missouri instructing him to seek redress at the law but not to sell any Jackson County lands.

Dec. 6, 1833

The Missouri elders petition Governor Dunklin for assistance in restoring them to their homes, for military protection, and for a court of inquiry once it is safe for Mormons to testify. This includes the statement that the protection of the Saints in Jackson County by force of the militia must be made to last until the Saints can receive “strength from our friends to protect ourselves.” (HC 1:452)

Dec. 10, 1833

Joseph writes to the persecuted Saints in Missouri, stating that “when we learn your sufferings, it awakens every sympathy of our hearts; it weighs us down; we cannot refrain from tears, yet we are not able to realize, only in part, your sufferings.” (HC 1:453-56)

Dec. 12, 1833

A letter arrives stating that the Saints who had moved to Van Buren County will also be drive from there.

Dec. 15, 1833

W. W. Phelps writes to Joseph that Gov. Dunklin will restore the Saints to Jackson County, but that he has no constitutional power to protect the Saints once they have been restored to the county, and the mob is swearing to kill them if they return. (There is evidence that this becomes the underlying motivation for the march of Zion’s Camp in May 1834 - to protect the Saints once they have been restored, not to restore them by force, as is commonly supposed. See BYU, Su ‘74, 406-20.)

Dec. 16, 1833

Joseph receives D&C 101. (pp. 46-49)

In their book Joseph Smith and the Doctrine & Covenants, Milton V. Backman, Jr. and Richard O. Cowan shed more light on the historical background for this section:

CONFLICT IN JACKSON COUNTY: Doctrine and Covenants 97-101

Doctrine and Covenants 97, 98, and 101 were given in Ohio, but they are concerned more with events in Missouri.

COUNSEL TO THE PERSECUTED SAINTS

Early in July 1833 hundreds of the Saints’ enemies, including some of the most prominent religious, political, and economic leaders of Jackson County, signed a “secret constitution,” which Latter-day Saints called “the manifesto of the mob.” This document ordered the Mormons immediately to close their merchandizing stores, discontinue printing operations, stop further immigration, and leave Jackson County. An unusual aspect of this document was a list of grievances that the mob used to justify its actions. The manifesto described the Latter-day Saints as “fanatics, or knaves, (for one or the other they undoubtedly are)” who pretend “to hold personal communication and converse face to face with the Most High God; to receive communications and revelations direct from heaven; to heal the sick by laying on hands; and, in short, to perform all the wonder-working miracles wrought by the inspired Apostles and Prophets of old.” Therefore, they vowed to remove the Mormons from their society, “peaceably if we can, forcibly if we must” (History of the Church, 1:374-76).

According to Parley P. Pratt, when Latter-day Saint leaders refused to agree to the terms of the manifesto, “the mob met at the court house on the 20th of July, and proceeded immediately to demolish the brick printing office and dwelling house of W. W. Phelps & Co., and destroyed or took possession of the press, type, books and property of the establishment; - at the same time turning MRs. Phelps and children out of doors: after which they proceeded to personal violence by a wonton assault and battery upon the Bishop of the church, Mr. Edward Partridge, and a Mr. [Charles] Allen, whom they tarred and feathered, and variously abused. They then compelled Messrs. Gilbert[,] Whitney & Co. to close their store and pack their goods” [History of Persecution, p. 7]. Copies of the nearly completed Book of Commandments were rescued courageously by two teenage Mormon girls (see Chapter 1).

When the Prophet received Doctrine and Covenants 97 and 98 about two weeks later in Ohio, he was not yet aware of how the mob had abused Church members and destroyed their property. Joseph could have known only by revelation that persecution had intensified. In these revelations, he was inspired to counsel the Saints not to neglect the temple, to be pure in heart, to renounce war, and refrain from seeking revenge.

THE SAINTS ARE EXPELLED FROM JACKSON COUNTY

When the leaders of the Missourians learned that the Latter-day Saints would not comply with the terms of the “manifesto,” mobs again attacked, burning homes and beating Saints. Governor Daniel Dunklin called out the militia to establish peace, but they seized only the Mormons’ guns and allowed the Saints’ enemies to renew their depredations. Finally, in early November 1833, approximately one thousand Latter-day Saints were driven by mobs from Jackson County. In one of the first accounts of events that had preceded the expulsion of Saints from Jackson County, Parley P. Pratt stated:

“On Friday, the first of November, women and children sallied forth from their gloomy retreats, to contemplate, with heart-rending anguish, the ravages of a ruthless mob, in the mangled bodies of their husbands, and in the destruction of their houses and furniture. Houseless, and unprotected by the arm of civil law in Jackson County - the dreary month of November staring them in the face, and loudly proclaiming a more inclement season at hand - the continual threats of the mob, that they would drive every Mormon from the county - and the inability of many to remove because of their poverty, caused an anguish of heart indescribable.

“These outrages were committed about two miles from my residence. News reached me before day-light the same morning, and I immediately repaired to the place, and was filled with anguish at the awful sight of houses in ruins, and furniture destroyed and strewed about the streets; women, in different directions, were weeping and mourning, while some of the men were covered with blood from the blows they had received from the enemy; others were endeavoring to collect the fragments of their scattered furniture, beds, &c….

“The same night [Friday] a party in Independence commenced stoning houses, breaking down doors and windows, destroying furniture, &c. This night the brick part of a dwelling house belonging to A. S. Gilbert, was partly demolished, and the windows of his dwelling broken in, while a gentleman lay sick in his house.

“The same night, the doors of the house of Messrs. Gilbert & Whitney were split open, and the goods strewed in the street, to which fact upwards of twenty witnesses can attest.

“After midnight a party of our men marched for the store, &c., and when the mob saw them approach, they fled. But one of their number, a Richard McCarty, was caught in the act of throwing rocks in at the door, while the goods lay strung around him in the street. He was immediately taken before Samuel Weston, Esq. and a warrant requested, that said McCarty might be secured; but his justiceship refused to do any thing in the case, and McCarty was then liberated.

“… Saturday night a party of the mob made an attack upon a settlement about six miles west of town. Here they tore the roof from a dwelling, broke open another house, found the owner, Mr. David Bennett, sick in bed. Him they beat inhumanly, and swore they would blow his brains out, and discharging a pistol, the ball cut a deep gash across the top of his head. In this skirmish one of their men was shot in the thigh” (History of Persecution, pp. 8-9).

At least one miracle occurred during a battle between the Latter-day Saints and their enemies. Philo Dibble recounted being shot and bleeding inwardly until his body was filled with blood: “I was then examined by a surgeon who … said that he had seen a great many men wounded, but never saw one wounded as I was that ever lived. He pronounced me a dead man.

“David Whitmer, however, sent me word that I should live and not die, but I could see no possible chance to recover. After the surgeon had left me, Brother Newell Knight came to see me, and sat down on the side of my bed. He laid his right hand on my head, but never spoke. I felt the Spirit resting upon me at the crown of my head before his hand touched me, and I knew immediately that I was going to be healed. It seemed to form like a ring under the skin, and followed down my body. When the ring came to the wound, another ring formed around the first bullet hole, also the second and third. Then a ring formed on each should and on each hip, and followed down to the ends of my fingers and toes and left me. I immediately arose and discharged three quarts of blood or more, with some pieces of my clothes that had been driven into my body by the bullets. I then dressed myself and … from that time not a drop of blood came from me and I never afterwards felt the slightest pain or inconvenience from my wounds, except that I was somewhat weak from the loss of blood” (Faith Promoting Classics, pp. 85-85).

A most descriptive account of the tragic exodus of the Saints from Jackson County was written by Parley P. Pratt: “Thursday, November 7th, the shore began to be lined on both sides of the ferry with men, women, children, goods, wagons, boxes, chests, provisions, & c., while the ferry men were very busily employed in crossing them over; and when night again closed upon us, the wilderness had much the appearance of a camp meeting. Hundreds of people were seen in every direction - some in tents and some in the open air, around their fires, while the rain descended in torrents. Husbands were inquiring for wives, and women for their husbands; parents for children, and children for parents. Some had had the good fortune to escape with their families, household goods and some provisions: while others knew not the fate of their friends, and had lost all their goods. The scene was indescribable” (History of Persecution, p. 12).

Orange Wight, the son of Lyman Wight, remembered that after crossing the Missouri River, some of his family camped near a big sycamore log six feet in diameter. He and others “laid a few poles on one side on the top of the log” and placed the other end on the ground. Then they spread a quilt or two on the poles. “Under the quilts and poles by the side of the big log” his brother, Lehi Lyman Wight, was born. At that time, he added, a mob was chasing his father, threatening to kill him, and the family was almost in a state of starvation. For three weeks the family lived in fear, not knowing the fate of their father. Orange testified that the Lord then answered their prayers. Their father evaded the mobs, crossed the river, and located his family. Meanwhile, one of the Church members, John Higbee, secured an old flintlock gun (Missourians had previously seized the guns of the Mormons) and shot eleven deer. Members also found wild bee trees. “Hence,” Orange concluded, “we lived on venison and honey” (“Autobiography,” pp. 1-2).

The Saints built temporary homes as best they could, searching out and making habitable all the old shanties and hovels that could be found, endeavoring to keep as close together as possible. Edward Partridge and Elder John Corrill “procured an old log cabin that had been used for a stable and cleaned it up as best they could.” The floor in this one-room cabin was nearly torn up, and Emily Partridge remembered that “the rats and rattlesnakes were too thick for comfort.” Blankets were hung a few feet from the fireplace and the two families, fifteen or sixteen in number, gathered near the fire to keep from freezing. John Corrill’s family occupied one side of the fireplace and Edward Partridge’s the other. Emily added that “our beds were in the back part of the room” which reminded her of the “polar regions” (Woman’s Exponent, 15 Feb. 1885, p. 138).

In December, after the Prophet learned of the expulsion, he inquired of the Lord and learned why the Lord had not intervened in the Saints’ behalf. The Lord chastised the converts for their transgressions but assured them that he had not forgotten them. They still needed to prepare for the Millennium, and, through parables, the Lord told them what to do. The Saints were to maintain their interest in Missouri.

THE SAINTS’ INTEREST IN ZION CONTINUES

The exiles crossed the Missouri River from Jackson County into Clay County, and most settled there. When the Latter-day Saints established schools, some of the earlier settlers of Clay County sent their children to attend classes there. “Of course,” Emily Partridge wrote, these children “were better dressed than the Mormon children, which caused them to sometimes sneer and make fun of our shabby clothes, but generally we got along very well. The Saints were very poor, and I sometimes wonder how they provided for their families the necessaries of life. My father being Bishop made the times much harder for him, for he not only had his family to provide for, but he had the poor to look after and provide for their comfort also” (Woman’s Exponent, 15 Feb. 1885, p. 138).

Not all of the Saints moved from Jackson County to Clay County. Thomas Marsh located in Lafayette County, where he taught school. Others went to Ray and Van Buren counties. “We scattered in every direction,” one Saint wrote. After moving to Van Buren County, some members were invited to settle in Clay County, where they “were treated with the utmost kindness” (Millennial Star, 11 July 1881, p. 439)

The migration of Latter-day Saints from other states to wester Missouri continued after the expulsion of the Mormons from Jackson County. Edward Stevenson arrived in Clay County, a lonely teenaged boy from southern Michigan. Leaving what he referred to as a “desirable” situation - his mother, who had been recently widowed, owned a comfortable home and 240 acres of good land - he packed his belongings in a small box and, with only one dollar in his pocket, started walking alone toward Zion. He soon joined with other converts from Michigan who were heading to western Missouri and arranged with a family to drive their ox team. After arriving in Clay County, young Edward found himself alone amid strangers, but he was impressed with the new land. (“Autobiography,” pp. 8-9).

In harmony with the Lord’s counsel given in Doctrine and Covenants 101, Church members continued to gather in the Missouri frontier in anticipation for the day when Zion would be redeemed. (pp. 89-94)

B. H. Roberts wrote an entire book on The Missouri Persecutions. The year 1833 was a very significant moment in the early history of the Church and in the history of the United States. It was a formative stage in the development of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the culture of the Church. The persecution of the Mormons in Missouri is also a hotly-debated topic. Clearly the persecutions against the innocent Saints was unjust and in many cases downright evil. The violence against the Mormons in Missouri is a terrible stain on the state of Missouri and a mark of the wickedness of many of the inhabitants of the state at that time.

While it is true that Mormonism appeared threatening to some American citizens, and while it is also true that there were a variety of motivations that led to the expulsion of the Saints from Missouri, the injustices and evils perpetrated against the Saints have been, and ought ever to be, thoroughly condemned. No matter how sophisticated the arguments, no true Christian or patriotic American who reveres the Constitution can, in good conscience, lay the blame for what happened to the Mormons in Missouri entirely upon Joseph Smith and his followers.

In his book The Revelations of the Prophet Joseph Smith, Lyndon W. Cook sheds more light on the historical background for this section:

Date. 16 December 1833.

Place. Kirtland, Geauga County, Ohio.

Historical Note. In accordance with a “secret constitution” authored and circulated by anti-Mormons in Jackson County, Missouri, a mob gathered in Independence Square on Saturday, 20 July 1833, and demanded “the discontinuance of the Church printing establishment,” the closing of the Gilbert-Whitney store, and “the cessation of all mechanical labors.”

When Church members refused to comply, the rabble destroyed the Church printing office and tarred and feathered two Mormons. Three days later, Church leaders were forced to sign a written agreement to leave the county by 1 January 1834. Oliver Cowdery was promptly sent to Kirtland to inform the Prophet of the riot. Upon his arrival, sometime before 18 August 1833, a meeting was convened to hear the matter. It was decided “that measures should be immediately taken to seek redress by the laws of our country.” After dispatching Orson Hyde and John Gould to Independence with the decision of the council, the Prophet corresponded with leaders of the Church in Missouri concerning their plight:

“In fellowship and love towards you, but with a broken heart and contrite spirit I take the pen to address you, but I know not what to say to you and the thought that this letter will be so long coming to you my hearts faints within me …. The Church in Kirtland concluded with one accord to die with you or redeem you and never at any time have I felt as I now feel that pure love and for you my brethren the warmth and zeal for your safety …. Brother Oliver is now sitting before me and is faithful and true and his heart bleeds as it were for Zion, yea, never did the heart pant for the cooling stream as doth the heart of thy Brother Oliver for thy salvation …. This affliction is sent upon us not for your sins, but for the sins of the Church and that all the ends of the earth may know that you are not speculating with them for lucre, but you are willing to die for the Church you have espoused.”

Upon petitioning the Missouri governor for assistance, Church leaders were urged by. the state attorney-general to seek both redress and protection under the law. This attempt to normalize conditions produced a vehement response from members of the opposition. The intransigence of non-Mormons in Jackson County was immediately made manifest when, on 31 October 1833, citizens demolished houses and whipped several Mormon men. Violence continued, and judges repeatedly refused ot issue warrants against the mobsters. On 4 November 1833 a skirmish on the Big Blue River caused the deaths of one Mormon and two Missourians.

As early as 25 November 1833 Hyde and Gould had returned to Kirtland bearing the tragic news of the Missouri mobbings and bloodshed. And on 10 December 1833 the Prophet learned by letter of the Saints’ flight from Jackson County by force.

Section 101, received on 16 December 1833, explained the reasons for the Saints’ expulsion from Zion. Moreover, it reiterated the command to purchase land in Jackson and adjoining counties and contained a parable which adumbrated the march of Zion’s Camp to rescue the homeless Saints.

Publication Note. Section 101 was first published in December 1833 or January 1834 on a broadside and was included as section 97 in the 1835 edition of the Doctrine and Covenants. (pp. 205-206)

In his chapter “Waiting for the Word of the Lord” in Revelations in Context, my friend David Grua describes the historical background for this section as follows:

“After Much Tribulation Cometh the Blessing”

Taking counsel from Joseph’s revelations, Missouri Church leaders worked to find legal protection from the mob and from its demand that they leave by spring. In September and October 1833, they sought redress from state officials and hired attorneys to represent the Latter-day Saints’ cause in the courts. The Saints’ legal actions had convinced the mob that Church members wouldn’t leave unless driven out. Before their case could be heard in court, mob violence broke out again.

In late October and early November, Jackson County vigilantes threatened the Saints and then drove them from their homes. Although Church members made some effort to defend themselves, they evidently sought to follow the Lord’s counsel in the August 6 revelation (Doctrine and Covenants 98) to endure their persecutions patiently.13 On November 6 and 7, while living as a refugee in Clay County, just north of Jackson County, Phelps wrote the first detailed account to Joseph Smith of the violence, describing beatings of Church members, destruction of their houses, and even bloodshed on both sides. He signed it, “Yours in affliction.”14 Over the next week, as Phelps continued to think about what had happened, a passage from the New Testament came to his mind. “The Savior said, Blessed are ye when ye are hated of all men for my name’s sake,” he wrote on November 14, “and I think we have come to that.”15

As this letter and other reports of the expulsion trickled into Kirtland in late November and early December, Joseph Smith prayerfully sought the revelatory guidance that Phelps and other Saints desperately desired. In a December 10 letter, Joseph reminded Church leaders in Missouri that in 1831 the Lord had previously warned Church members “that after much tribulation cometh the blessing.” Although the Lord had not yet revealed why the “great calamity” had “come upon Zion” or “by what means he [the Lord] will return her back to her inheritance,” Joseph remained confident that Zion would be redeemed in God’s “own due time.” The Prophet advised the Saints not to sell their lands in Zion and encouraged them to seek legal redress from state and federal officials. If the government failed the Saints, they were to plead with the Lord “day and night” for divine justice. Joseph concluded with a prayer that God would remember His promises regarding Zion and deliver the Saints.16

On December 16 and 17, Joseph dictated an extended revelation, now Doctrine and Covenants 101, that provided answers to the questions that he, Phelps, and other Saints had been asking. The Lord had allowed the calamity to occur “in consequence of their [the Saints’] transgressions.” Nevertheless, the Lord stated, “Notwithstanding their sins my bowels are filled with compassion towards them.” Although the Saints were scattered, Zion would “not be moved out of her place.” Concerning Zion’s redemption, the revelation related a parable of “a certain noble[man]” who had commissioned his servants to protect his vineyard. While the servants disputed among themselves, “the enemy came by night” and “distroyed their works and broke down the Olive trees.” The Lord commanded his servant to “take all the strength of mine house” and “redeem my vineyard.” Reiterating the affirmation of the U.S. Constitution from Doctrine and Covenants 98, the revelation repeated Joseph Smith’s earlier counsel that the Missouri Saints seek redress from civil authorities, with a promise that if government officials rejected Church members’ pleas, the Lord would “come forth out of his hiding place & in his fury vex the nation.”17 Doctrine and Covenants 101 provided the Prophet a divinely inspired plan for Zion’s redemption—a project that would occupy his attention for the remainder of his life.18

By early 1834, a copy of the revelation that would become Doctrine and Covenants 101 had arrived in Missouri, providing William W. Phelps the “word of the Lord”19 that he had been waiting for. On February 27, he wrote to Joseph Smith, updating him on the Saints’ efforts to receive justice in the Missouri court system. As Phelps closed his letter, he alluded to the revelation. Phelps wondered if “the servants of the Lord of the vineyard, who are called and chosen to prune it for the last time” would “fear to do as much for Jesus as he did for us”? “No,” he answered, “we will obey the voice of the Spirit, that good may overcome the world.”20 (pp. 198-200)

The authors of the online resource Joseph Smith’s Revelations: A Doctrine and Covenants Study Companion from the Joseph Smith Papers add this thorough description of the historical background for D&C 101:

Revelation, 16–17 December 1833

Source Note

Revelation, Kirtland Township, OH, 16–17 Dec. 1833. Featured version copied [between ca. Dec. 1833 and Jan. 1834] in Revelation Book 2, pp. 73–83; handwriting of Frederick G. Williams; Revelations Collection, CHL. For more information, see the source note for Revelation Book 2 on the Joseph Smith Papers website.

Historical Introduction

On 16–17 December 1833, JS dictated a revelation that addressed the November 1833 expulsion of church members from Jackson County, Missouri, and explained the steps they should take to regain their lands. After members of the Church of Christ settled in Jackson County, conflicts between them and their neighbors quickly developed. After incidents of violence occurred in July 1833, including the destruction of the church’s printing office and the tarring and feathering of Edward Partridge, church leaders, hoping to quell the attacks on their people, promised to move church members from Jackson County in two phases: half would leave by January 1834, and the other half would leave by April 1834.1 However, in August 1833, JS counseled Missouri church members to not sell “one foot of land” in Jackson County, stating that God would “spedily deliver Zion.”2 Thereafter, church leaders in Missouri petitioned Governor Daniel Dunklin for protection while they pursued litigation against their assailants. After hearing of the Saints’ efforts to seek protection and prosecute their attackers, other residents believed that the church members were not planning to leave as expected. Other settlers organized themselves and attacked the homes of members of the Church of Christ in late October and early November 1833. A group of Saints confronted their assailants on 4 November, killing two of them, but a militia (consisting of many who were antagonistic to the members of the Church of Christ) confiscated the Saints’ weapons, and within a few days, most church members were driven from Jackson County.3

On 25 November 1833, JS heard a verbal account about the “riot in Zion” from Orson Hyde and John Gould, who witnessed the violence.4 On 10 December, JS received letters from Edward Partridge, John Corrill, and William W. Phelps, all giving more details about the events in Missouri and asking for counsel about what church members in Missouri should do.5 “We are in hopes that we shall be able to return to our houses & lands before a grea[t] while,” Partridge wrote, “but how this is to be accomplished is all in the dark to us as yet.” Partridge had little faith in receiving help from the executive or the judicial system, as they had proved ineffective in preventing the expulsion. He therefore believed that church members would probably return to Jackson County only through “the interposition of God.” He feared, too, that the expulsion was the beginning of church members being “driven from city to city & from sinagouge to sinagouge.” Understanding that JS had counseled church leaders to retain their lands in Jackson County, Partridge declared that he did not want to sell, but “if we are to be driven about for years I can see no use in keeping our possessions here.” Facing these circumstances, Partridge requested “wisdom & light” from JS “on many subjects.”6

As details of the violent events in Missouri reached Kirtland, Ohio, in late fall, JS pleaded to God for answers as to why church members were expelled from Jackson County, what it meant for the gathering to Zion, and what church members should do to regain their lands.7 On 5 December 1833, he wrote to Partridge, telling him that if initial reports that church members had surrendered and were evacuating Jackson County were incorrect, they were to “maintain the ground as Long as there is a man Left,” since it was “the place appointed of the Lord for your inheritance.” Partridge could purchase land in Clay County for a temporary place of refuge but was not to sell land in Jackson County. JS also urged Partridge “to use every lawful means in your power to seek redress for your grievances of your enemies and prosecute them to the extent of the Law.” Such means included petitioning judges, the governor, and the president of the United States for aid.8 Five days later, JS informed Missouri church leaders that the Lord was keeping “hid” from him the larger issues of how Zion would be redeemed, when such redemption would occur, and “why God hath suffered so great calamity to come upon Zion.” The voice of the Lord would only say to him, “Be still, and know that I am God!”9

The 16–17 December 1833 revelation featured here provided the direction that JS and other church leaders sought. The revelation gave clear reasons for the ejection of Missouri church members from Jackson County, stating that they were expelled because of their transgressions. Yet the revelation also provided hope that the Lord would be merciful to the Missouri church members and that Zion would not be moved out of her place. It reiterated that church members were not to sell their lands in Jackson County and that they were to seek redress through the judicial system, the governor of Missouri, and the president of the United States. Through a parable of a nobleman and his vineyard, the revelation indicated how members of the church were to reclaim their lands: by gathering up the “strength of mine house which are my wariors my young men and they that are of middle age” and sending them to Zion to redeem it. In addition, branches of the church outside of Missouri were to continue to raise money for land purchases and to gather to the area, thereby strengthening the church’s membership in Zion.

Details behind the immediate circumstances of the revelation are scant. According to a later account from Ira Ames, a church member living in Kirtland at the time, the revelation came to JS and Oliver Cowdery over the course of one night. Ames explained that he and Martin Harris went to JS’s house in Kirtland early one December morning and “found Joseph and Oliver Cowdry at breakfast.” Cowdery greeted the two by saying, “Good morning Brethren, we have just received news from heaven.” That news was the revelation featured here, the manuscript copy of which was lying on the table.10 Ames did not give the specific date of this encounter, and the earliest known copy of the revelation—made by Frederick G. Williams in Revelation Book 2 soon after the revelation’s dictation—also provided no date. Sometime before 24 January 1834, the church’s printing office in Kirtland published a broadsheet of the revelation, again without a date.11 A copy that John Whitmer made sometime in 1834 in Revelation Book 1, however, dated the revelation to 16–17 December 1833; a copy of the revelation in the journal of George Burket, probably made in 1835, bears that same date.12

Although it is possible that David W. Patten and William Pratt took a copy of the revelation with them to Missouri when they left Kirtland on 19 December 1833, carrying “dispatches” for the Missouri church leaders,13 it appears that JS first sent the revelation to Missouri in a letter dated 22 January 1834.14 According to a 24 January 1834 article in the Painesville Telegraph, the printed broadsheet of the revelation had also been “privately circulated” among church members.15 According to Eber D. Howe, editor of the Telegraph and one of JS’s detractors, “The publication of this proclamation … was taken up by all their priests and carried to all their congregations, some of which were actually sold for one dollar per copy.”16 Church leaders also included the revelation in a petition they sent to Missouri governor Daniel Dunklin, and they planned to send it with a petition to President Andrew Jackson, although it is unclear whether the revelation was ever sent to the president.17 In February 1834, JS began implementing the revelation’s instructions to gather up the strength of the Lord’s house, declaring that he “was going to Zion to assist in redeeming it” and requesting “volunteers to go with him.”18 For the next several weeks, JS and others recruited participants for what was called the Camp of Israel, and in May 1834 the expedition started for Missouri.19

The authors of the first volume of Saints (see here, here, and here) add these details to our understanding of the historical background for this section:

For days following the meteor shower, Joseph expected something miraculous to happen. But life continued as normal, and no other signs appeared in the heavens. “My heart is somewhat sorrowful,” he confided in his journal. More than three months had passed since the Lord had revealed anything for the Saints in Zion, and Joseph still did not know how to help them. The heavens seemed closed.

Adding to Joseph’s anxiety, Doctor Philastus Hurlbut had recently returned from Palmyra and Manchester with stories—some false, others exaggerated—about Joseph’s early life. As the stories spread around Kirtland, Hurlbut also swore he would wash his hands in Joseph’s blood. The prophet soon began using bodyguards.

On November 25, 1833, a little more than a week after the meteor shower, Orson Hyde arrived in Kirtland and reported on the Saints’ expulsion from Jackson County. The news was harrowing. Joseph did not understand why God had let the Saints suffer and lose the promised land. Nor could he foresee Zion’s future. He prayed for guidance, but the Lord simply said to be still and trust in Him.

Joseph wrote Edward Partridge immediately. “I know that Zion, in the own due time of the Lord, will be redeemed,” he testified, “but how many will be the days of her purification, tribulation, and affliction, the Lord has kept hid from my eyes.”

With little else to offer, Joseph tried to comfort his friends in Missouri, despite the eight hundred miles between them. “When we learn of your sufferings, it awakens every sympathy of our hearts,” he wrote. “May God grant that notwithstanding your great afflictions and sufferings, there may not anything separate us from the love of Christ.”

This is Smith’s and Sjodahl’s introduction to this section:

In his letter to the scattered Saints in Missouri, dated December 10th, 1833, the Prophet stated that the spirit withheld from him definite knowledge of the reason why the calamity had fallen upon Zion. Here is another striking evidence of his sincerity. If he had been in the habit of writing revelations without divine inspiration, he could have done so at this time. But it is perfectly evident that he did not speak in the name of the Lord except when prompted to do so by the Spirit. On the 16th of December, however, this Revelation was received concerning the Saints in Zion, and the Lord (1) states why they had been afflicted (1-3); (2) explains the twofold object of the experience they had passed through (4-8); (3) gives promises concerning the Saints (9-21); (4) commands them to gather (22-5); (5) speaks of the final victory (26-36); (6) reminds them that they are “the Salt of the Earth” (37-42); (7) and that Zion will be redeemed (43-62); (8) sends special instructions to the Church (63-75); (9) and to the scattered Saints (76-80); (10) applies the parable of the unjust judge (89-95); and (11) closes with instructions and promises (96-101). (p. 637)

Monte S. Nyman introduces this section as follows:

Historical Setting:

“December 12, [1833] - An express … from Van Buren county, with information that those families, which had fled from Jackson County, and located there, were about to be driven from that county, after building their houses and carting their winter’s store of provisions, grain, etc. forty or fifty miles. Several families are already fleeing from thence …. The destruction of crops, household furniture, and clothing is very great, and much of their stock is lost. The main body of the church is now in Clay county, where the people are as kind and accommodating as could reasonably be expected. The continued threats of death to individuals of the Church, if they make their appearance in Jackson county, prevent the most of them, even at this day, from returning to that county, to secure personal property, which they were obliged to leave in their flight.” [HC, 1:456-57]

“December 16 - I [Joseph Smith] received [Doctrine and Covenants 101].” [HC, 1:458]. (p. 287)

This is Bruce R. McConkie’s section heading for this section:

Revelation given to Joseph Smith the Prophet, at Kirtland, Ohio, December 16 and 17, 1833. At this time the Saints who had gathered in Missouri were suffering great persecution. Mobs had driven them from their homes in Jackson County; and some of the Saints had tried to establish themselves in Van Buren, Lafayette, and Ray Counties, but persecution followed them. The main body of the Saints was at that time in Clay County, Missouri. Threats of death against individuals of the Church were many. The Saints in Jackson County had lost household furniture, clothing, livestock, and other personal property; and many of their crops had been destroyed.

The History of the Church contains this record of the events that pertain to this section:

Expulsion of the Saints from Jackson County. [Sidenote: Attack on the Saints Settled on Big Blue.] Thursday night, the 31st of October, gave the Saints in Zion abundant proof that no pledge on the part of their enemies, written or verbal, was longer to be regarded; for on that night, between forty and fifty persons in number, many of whom were armed with guns, proceeded against a branch of the Church, west of the Big Blue, and unroofed and partly demolished ten dwelling houses; and amid the shrieks and screams of the women and children, whipped and beat in a savage and brutal manner, several of the men: while their horrid threats frightened women and children into the wilderness. Such of the men as could escape fled for their lives; for very few of them had arms, neither were they organized; and they were threatened with death if they made any resistance; such therefore as could not escape by flight, received a pelting with stones and a beating with guns and whips. On Friday, the first of November, women and children sallied forth from their gloomy retreats, to contemplate with heartrending anguish the ravages of a ruthless mob, in the lacerated and bruised bodies of their husbands, and in the destruction of their houses, and their furniture. Houseless and unprotected by the arm of the civil law in Jackson county, the dreary month of November staring them in the face and loudly proclaiming an inclement season at hand; the continual threats of the mob that they would {427} drive every “Mormon” from the county; and the inability of many to move, because of their poverty, caused an anguish of heart indescribable. [Sidenote: The Saints at the Prairie Settlement Attacked.] On Friday night, the 1st of November, a party of the mob proceeded to attack a branch of the Church settled on the prairie, about twelve or fourteen miles from the town of Independence. Two of their number were sent in advance, as spies, viz., Robert Johnson, and ---- Harris, armed with two guns and three pistols. They were discovered by some of the Saints, and without the least injury being done to them, said mobber Robert Johnson struck Parley P. Pratt over the head with the breach of his gun, after which they were taken and detained till morning; which action, it was believed, prevented a general attack of the mob that night. In the morning the two prisoners, notwithstanding their attack upon Parley P. Pratt the evening previous, were liberated without receiving the least injury. [1] [Sidenote: Mobbings at Independence.] The same night, (Friday), another party in Independence commenced stoning houses, breaking down doors and windows and destroying furniture. This night the brick part attached to the dwelling house of A. S. Gilbert, was partly pulled down, and the windows of his dwelling broken in with brickbats and rocks, while a gentleman, a stranger, lay sick with fever in his house. The same night three doors of the store of Messrs. Gilbert & Whitney were split open, {428} and after midnight the goods, such as calicos, handkerchiefs, shawls, cambrics, lay scattered in the streets. An express came from Independence after midnight to a party of the brethren who had organized about half a mile from the town for the safety of their lives, and brought the information that the mob were tearing down houses, and scattering goods of the store in the streets. Upon receiving this information the company of brethren referred to marched into Independence, but the main body of the mob fled at their approach. One Richard McCarty, however, was caught, in the act of throwing rocks and brickbats into the doors, while the goods lay scattered around him in the streets. He was immediately taken before Samuel Weston, Esq., justice of the peace, and complaint was then made to said Weston, and a warrant requested, that McCarty might be secured; but Weston refused to do anything in the case at that time, and McCarty was liberated. [2] [Sidenote: Other Incidents at Independence.] The same night some of the houses of the Saints in Independence had long poles thrust through the shutters and sash into the rooms of defenseless women and children, from whence their husbands and fathers had been driven by the dastardly attacks of the mob, which were made by ten, fifteen, or twenty men upon a house at a time. Saturday, the 2nd of November, all the families of the Saints in Independence moved with their goods about half a mile out of town and organized to the number of thirty, for the preservation of life and personal effects. The same night a party from Independence met a party from west of the Blue, and made an attack upon a branch of the Church {429} located at the Blue, about six miles from the village of Independence. Here they tore the roof from one dwelling and broke open another house; they found the owner, David Bennett, sick in bed, and beat him most inhumanly, swearing they would blow out his brains. They discharged a pistol at him, and the ball cut a deep gash across the top of his head. In this skirmish a young man of the mob, was shot in the thigh; but by which party the shot was fired is not known. [Sidenote: An Appeal to the Circuit Court.] The next day, Sunday, November 3rd, four of the brethren, viz., Joshua Lewis, Hiram Page, and two others, [3] were dispatched for Lexington, to see the circuit judge, and obtain a peace warrant. Two other brethren called on Esquire Silvers, in Independence, and asked him for a peace warrant, but he refused to issue one on account, as he afterwards declared, of his fears of the mob. This day many of the citizens, professing friendship, advised the Saints to leave the county as speedily as possible; for the Saturday night affray had enraged the whole county, and the people were determined to come out on Monday and massacre indiscriminately; and, in short, it was commonly declared among the mob, that “_Monday would be a bloody day_.” [Sidenote: Events of Monday, November 4th.] Monday came, and a large party of the mob gathered at the Blue, took the Ferry boat belonging to the Church, threatened lives, etc. But they soon abandoned the ferry, and went to Wilson’s store, about one mile west of the Blue. Word had been previously sent to a branch of the Church, several miles west of the Blue, that the mob were destroying property on the east side of the river, and the sufferers there wanted help to preserve lives and property. Nineteen {430} men volunteered, and started to their assistance; but discovering that fifty or sixty of the mob had gathered at said Wilson’s they turned back. At this time two small boys passed on their way to Wilson’s, who gave information to the mob, that the “Mormons” were on the road west of them. Between forty and fifty of the mob armed with guns, immediately started on horseback and on foot in pursuit; after riding about two or two and a half miles, they discovered them, when the said company of nineteen brethren immediately dispersed, and fled in different directions. The mob hunted them, turning their horses meantime into a corn field belonging to the Saints. Corn fields and houses were searched, the mob at the same time threatening women and children that they would pull down their houses and kill them if they did not tell where the men had fled. Thus they were employed in hunting the men and threatening the women, when a company of thirty of the brethren from the prairie, armed with seventeen guns, made their appearance. [4] [Sidenote: The Battle.] The former company of nineteen had dispersed, and fled, and but one or two of them returned in time to take part in the subsequent battle. On the approach of the latter company of thirty men, some of the mob Cried, “Fire, _G-- d-- ye_, fire.” Two or three guns were then fired by the mob, which fire was returned by the other party without loss of time. This company is the same that is represented by the mob as having gone forth in the evening of the above incident bearing the olive branch of peace. The mob retreated immediately after the first fire, leaving some of their horses in Whitmer’s corn field, and two of their number, Hugh L. Brazeale and Thomas Linvill dead on the ground. Thus fell Hugh L. Brazeale, who had been heard to say, “With ten fellows, I will wade to my knees in blood, but that I will drive the Mormons from Jackson county.” The next morning the {431} corpse of Brazeale was discovered on the battle ground with a gun by his side. Several were wounded on both sides, but none mortally among the brethren except Andrew Barber, who expired the next day. [5] This attack of the mob was made about sunset, Monday, November the 4th; and the same night, runners were dispatched in every direction under pretense of calling out the militia; spreading every rumor calculated to alarm and excite the uninformed as they went; such as that the “Mormons” had taken Independence, and that the Indians had surrounded it, the “Mormons” and Indians being colleagued together. [Sidenote: Gilbert _et al_ on Trial.] The same evening, November 4th--not being satisfied with breaking open the store of Gilbert & Whitney, and demolishing a part of the dwelling house of said Gilbert the Friday night previous--the mob permitted the said McCarty, who was detected on Friday night as one of the breakers of the store doors, to take out a warrant, and arrest the said Gilbert and others of the Church, for a pretended assault, and false imprisonment of said McCarty. Late in the evening, while the court was proceeding with their trial in the court house, a gentleman unconnected with the court, as {432} was believed, perceiving the prisoners to be without counsel and in imminent danger, advised Brother Gilbert and his brethren, to go to jail as the only alternative to save life; for the north door of the court house was already barred, and an infuriated mob thronged the house, with a determination to beat and kill; but through the interposition of this gentleman (Samuel C. Owens, clerk of the county court, so it was afterwards learned), said Gilbert and four of his brethren were committed to the county jail of Jackson county, the dungeon of which must have been a palace compared with a court room where dignity and mercy were strangers, and naught but the wrath of man as manifested in horrid threats shocked the ears of the prisoners. [Sidenote: Assault on the Prisoners.] The same night, the prisoners, Gilbert, Morley, and Corrill, were liberated from the jail, that they might have an interview with their brethren, and try to negotiate some measures for peace; and on their return to jail about 2 o’clock, Tuesday morning, in the custody of the deputy sheriff, an armed force of six or seven men stood near the jail and hailed them. They were answered by the sheriff, who gave his name and the names of the prisoners, crying, “_Don’t fire, don’t fire, the prisoners are in my charge_.” They, however, fired one or two guns, when Morley and Corrill retreated; but Gilbert stood, firmly held by the sheriff, while several guns were presented at him. Two, more desperate than the rest, attempted to shoot, but one of their guns flashed, and the other missed fire. Gilbert was then knocked down by Thomas Wilson, who was a grocer living at Independence. About this time a few of the inhabitants of the town arrived, and Gilbert again entered the jail, from which he, with three of his brethren, were liberated about sunrise, without further prosecution of the trial. William E. M’Lellin was one of the prisoners. [Sidenote: Incidents of the 5th of November.] On the morning of the 5th of November, Independence began to be crowded with individuals from different {433} parts of the county armed with guns and other weapons; and report said the militia had been called out under the sanction or at the instigation of Lieutenant Governor Boggs; and that one Colonel Pitcher had the command. Among this militia (so-called) were included the most conspicuous characters of the mob; and it may truly be said that the appearance of the ranks of this body was well calculated to excite suspicion of their horrible designs. [Sidenote: One Hundred Volunteers.] Very early on the same morning, several branches of the Church received intelligence that a number of their brethren were in prison, and the determination of the mob was to kill them; and that the branch of the Church near the town of Independence was in imminent danger, as the main body of the mob was gathered at that place. In this critical situation, about one hundred of the Saints, from different branches, volunteered for the protection of their brethren near Independence, [6] and proceeded on the road towards Independence, and halted about one mile west of the town, where they awaited further information concerning the movements of the mob. They soon learned that the prisoners were not massacred, and that the mob had not fallen upon the branch of the Church near Independence, as had been reported. They were also informed, that the militia had been called out for their protection; but in this they placed little confidence, for the body congregated had every appearance of a mob; and subsequent events fully verified their suspicions. [Sidenote: The Demands of the Mob-Militia.] On application to Colonel Pitcher, it was found that there was no alternative, but for the Church to leave the county forthwith, and deliver into his hands certain men to be tried for murder, said to have been committed by them in the {434} battle, as he called it, of the previous evening. The arms of the Saints were also demanded by Colonel Pitcher. Among the committee appointed to receive the arms of the brethren were several of the most unrelenting of the old July mob committee, who had directed in the demolishing of the printing office, and the personal injuries inflicted on brethren that day, viz., Henry Chiles, Abner Staples, and Lewis Franklin, who had not ceased to pursue the Saints, from the first to the last, with feelings the most hostile. These unexpected requisitions of the Colonel, made him appear like one standing at the head of both civil and military law, stretching his authority beyond the constitutional limits that regulate both civil and military power in our Republic. Rather than to have submitted to these unreasonable requirements, the Saints would have cheerfully shed their blood in defense of their rights, the liberties of their country and of their wives and children; but the fear of violating law, in resisting this pretended militia, and the flattering assurance of protection and honorable usage promised by Lieutenant Governor Boggs, in whom, up to this time, they had reposed confidence, induced the Saints to submit, believing that he did not tolerate so gross a violation of all law, as had been practiced in Jackson county. [7] But as so glaringly exposed in the sequel, it was the design and craft of this man to rob an innocent people of their arms by stratagem, and leave more than one thousand defenseless men, women and {435} children to be driven from their homes among strangers in a strange land to seek shelter from the stormy blast of winter. All earth and hell cannot deny that a baser knave, a greater traitor, and a more wholesale butcher, or murderer of mankind ever went untried, unpunished, and unhung--since hanging is the popular method of execution among the Gentiles in all countries professing Christianity, instead of blood for blood, according to the law of heaven. [8] The conduct of Colonels Lucas and Pitcher, had long proven them to be open and avowed enemies of the Saints. Both of these men had their names attached to the mob circular, as early as the July previous, the object of which was to drive the Saints from Jackson county. But with assurances from the Lieutenant Governor and others that the object was to disarm the combatants on both sides, and that peace would be the result, the brethren surrendered their arms to the number of fifty or upwards. [9] The men present, who were accused of being in the battle the evening before, also gave themselves up for trial; but after detaining them one day and a night on a pretended trial for murder, in which time they were threatened {436} and brick-batted, Colonel Pitcher, after receiving a watch of one of the prisoners to satisfy “costs of court,” took them into a corn field, and said to them, “_Clear_!” [Meaning, of course, clear out, leave.] [Sidenote: Savagery of the Mob.] After the Saints had surrendered their arms, which had been used only in self-defense, the tribes of Indians in time of war let loose upon women and children, could not have appeared more hideous and terrific, than did the companies of ruffians who went in various directions, well armed, on foot and on horseback, bursting into houses without fear, knowing the arms were secured; frightening distracted women with what they would do to their husbands if they could catch them; warning women and children to flee immediately, or they would tear their houses down over their heads, and massacre them before night. At the head of these companies appeared the _Reverend Isaac McCoy_, with a gun upon his shoulder, ordering the Saints to leave the county forthwith, and surrender what arms they had. Other pretended preachers of the Gospel took a conspicuous part in the persecution, calling the “Mormons” the “common enemy of mankind,” and exulting in their afflictions. [Sidenote: Events of 5th and 6th of November.] On Tuesday and Wednesday nights, the 5th and 6th of November, women and children fled in every direction before the merciless mob. One party of about one hundred and fifty women and children fled to the prairie, where they wandered for several days with only about six men to protect them. Other parties fled to the Missouri river, and took lodging for the night where they could find it. One Mr. Barnet opened his house for a night’s shelter to a wandering company of distressed women and children, who were fleeing to the river. During this dispersion of the women and children, parties of the mob were hunting the men, firing upon some, tying up and whipping others, and pursuing others with horses for several miles. {437} [Sidenote: Scenes on the Banks of the Missouri.] Thursday, November 7th, the shores of the Missouri river began to be lined on both sides of the ferry, with men, women and children; goods, wagons, boxes, chests, and provisions; while the ferrymen were busily employed in crossing them over. When night again closed upon the Saints, the wilderness had much the appearance of a camp meeting. Hundreds of people were seen in every direction; some in tents, and some in the open air, around their fires, while the rain descended in torrents. Husbands were inquiring for their wives, and women for their husbands; parents for children, and children for parents. Some had the good fortune to escape with their families, household goods, and some provisions; while others knew not the fate of their friends, and had lost all their effects. The scene was indescribable, and would have melted the hearts of any people upon earth, except the blind oppressor, and the prejudiced and ignorant bigot. Next day the company increased, and they were chiefly engaged in felling small cottonwood trees, and erecting them into temporary cabins, so that when night came on, they had the appearance of a village of wigwams, and the night being clear, the occupants began to enjoy some degree of comfort. [Sidenote: Lieutenant Governor Boggs.] Lieutenant Governor Boggs has been represented as merely a curious and disinterested observer of these events; [10] yet he was evidently the head and front of the mob; for as may easily be seen by what follows, no important move was made without his sanction. He certainly was the secret mover in the affairs of the 20th and 23rd of July; and, as will appear in the sequel, by his authority the mob was converted into militia, to effect by stratagem what he knew, as well as his hellish host, could not be done by legal force. As Lieutenant Governor, he had only to wink, and the mob went from maltreatment to murder. The {438} horrible calculations of this second Nero were often developed in a way that could not be mistaken. Early on the morning of the 5th, say at 1 o’clock a. m., he came to Phelps, Gilbert, and Partridge, and told them to flee for their lives. Now, unless he had given the order to murder no one would have attempted it, after the Church had agreed to go away. His conscience, however, seemed to vacillate at its moorings, and led him to give the secret alarm to these men. [11] [Sidenote: In Exile.] The Saints who fled from Jackson county, took refuge in the neighboring counties, chiefly in Clay county, the inhabitants of which received them with some degree of kindness. Those who fled to the county of Van Buren were again driven, and compelled to flee, and these who fled to Lafayette county, were soon expelled, or the most of them, and had to move wherever they could find protection. [12]

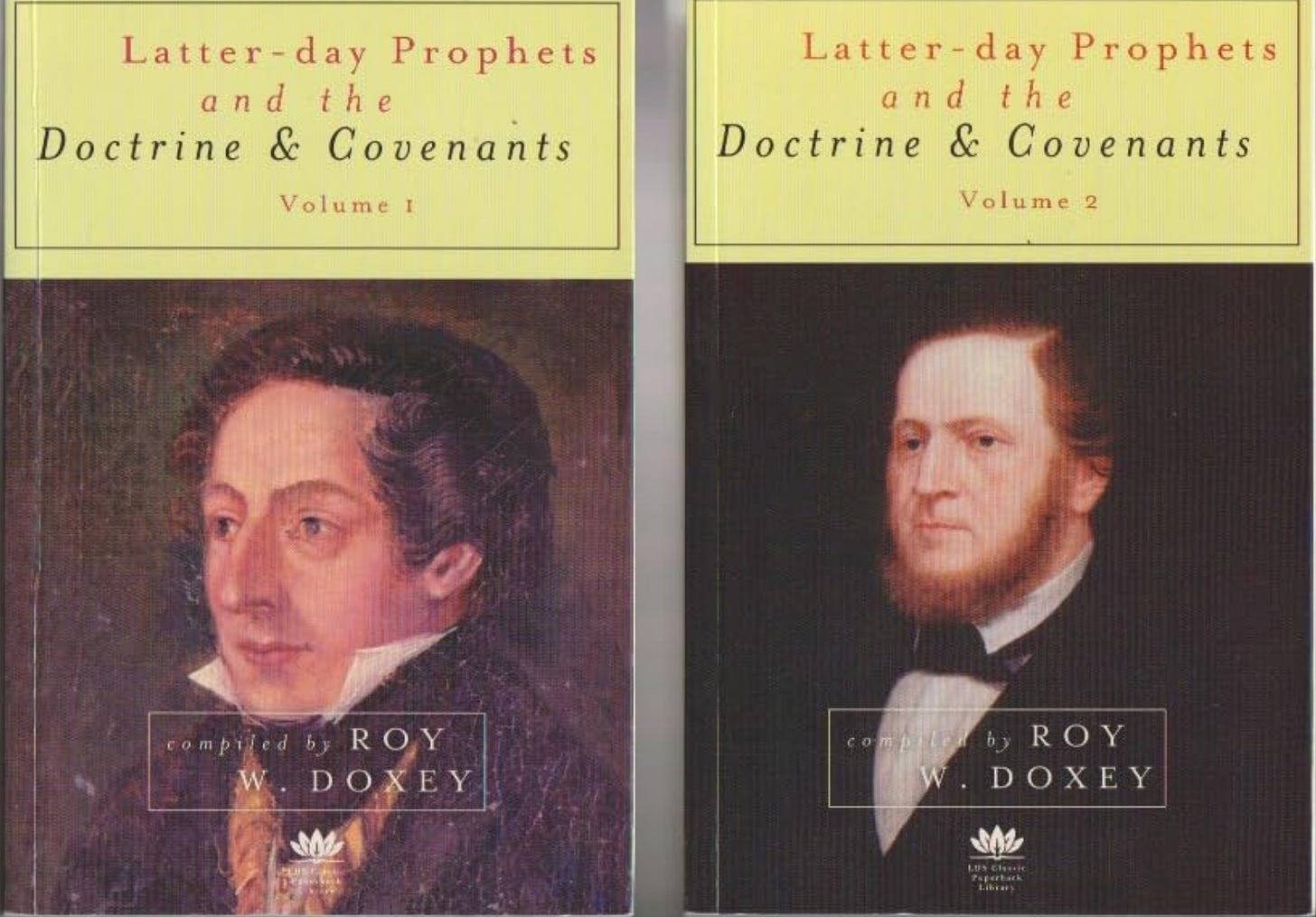

(See also Roy W. Doxey, Latter-day Prophets and the Doctrine & Covenants, Vol. 2, pp. 236-238)

With this historical background in mind, in the following posts we will examine and appreciate the revelation itself.