I created the “Kindled Critique” category of The Torch for book reviews and film reviews. What follows also fits into my categories “Athen’s Flame” and “The Hidden Flame.”

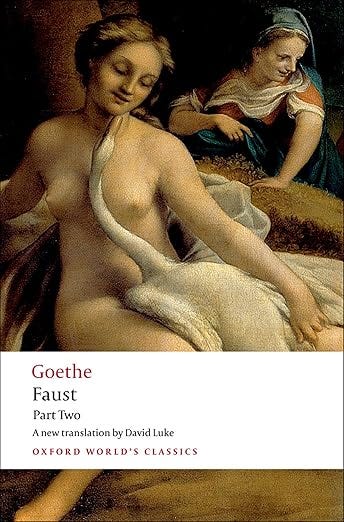

Most recently in the Provo Great Books Club (see here, here, and here) we’ve been reading Part Two of Goethe’s Faust (in the fantastic David Luke English translation, here and here).

We began by reading and discussing Marlowe’s play Doctor Faustus, followed by Part One of Goethe’s Faust. Tonight we will finish reading and discussing Act One of Part Two of Goethe’s Faust.

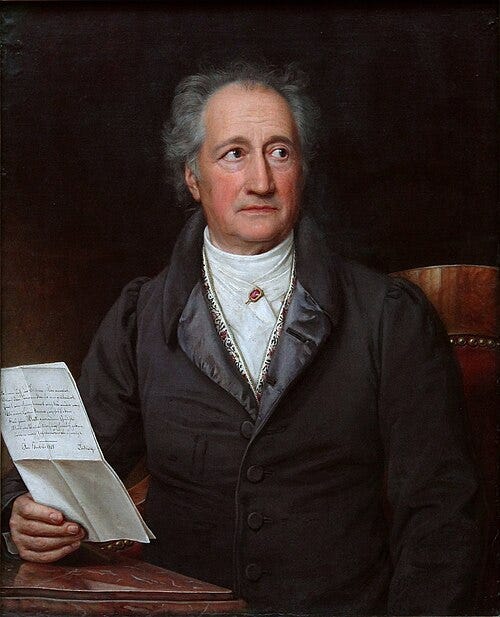

Part One of Goethe’s Faust was a whirlwind. Luke’s introductions and endnotes to his translations suggest that Goethe wrote esoterically. There are many contradictions, and seeming contradictions in Goethe’s masterpiece, which he wrote over a period of about fifty years. In fact, early in his book Philosophy Between the Lines: The Lost History of Esoteric Writing, Arthur M. Melzer quotes Goethe in support of his thesis that, even though this fact has been much neglected in modern times, prior to the nineteenth century, all philosophers, to one degree or another, wrote in an esoteric manner:

I have always considered it an evil, indeed a disaster which, in the second half of the previous century, gained more and more ground that one no longer drew a distinction between the exoteric and the esoteric.

As we discussed in our group, Goethe may have attempted to do for Germany what Homer had done for Greece, what Virgil and Dante had done for Italy, what Shakespeare and Milton had done for England (after Beowulf), and what perhaps has yet to be done for the United States of America, namely, to create a national epic. His debt to Homer, Virgil, Dante, Shakespeare, and Milton is clear, but Goethe’s genius has its own peculiar delights.

I read Goethe’s I dolori del giovane Werther (The Sorrows - or Suffering of Young Werther) in college while simultaneous studying Dante’s Divina Commedia, unaware of Goethe’s affinity for Dante. But ever since then (about two decades ago) I have wanted to read Goethe’s Faust. I better understand now why I might have been attracted to Goethe’s writings in my youth, and the more I learn about him, the more I am intrigued by his story and his intellectual development. I have also been particularly interested in the development of Goethe's religious beliefs (see also here, here, and here).

Throughout both parts of Faust, Goethe seems to respond to problems that he sees in both the Catholic and Protestant traditions (as well as the scholastic tradition) and interpretations of scripture. In some instances, Goethe seems to respond specifically to Martin Luther. This topic has been on my mind as a result of the recent Natural Law Colloquium in which I participated. (On a related note, although I don't agree with everything in her essay, this young lady does a great job of identifying and clarifying some of the major issues or tensions in Goethe's response to Luther.)

The translator of the edition of Faust that we are reading, David Luke, wrote an article entitled "Goethe's Attitude on Christian Belief," that might respond (if I could download it for free) to some of my questions. These are a few other articles on this topic that I have also begun to explore:

The following note in Wikepedia also helps to explain a lot about Goethe and Faust:

"Goethe was a Freemason, joining the lodge Amalia in Weimar in 1780, and frequently alluded to Masonic themes of universal brotherhood in his work.[106] He was also attracted to the Illuminati, a Bavarian secret society founded on 1 May 1776.[107][106]"

In any case, thus far it seems to me that although Faust is in some ways disturbing, Goethe was on the right track. As further evidence that he was on the right track, today I discovered (or was reminded) that Goethe was one of the eminent spirits who appeared to Wilford Woodruff in the St. George Temple.

In other words, Goethe is now a "Mormon."